The Post-War Consensus, Open Society, and the New World Order

Few understand that when they attack those who question the Post-War Consensus, they're defending a global, New World Order

If you could create a “word cloud” graphic of tweets, blog articles, and podcast topics in American evangelicalism for the last three months, one word would likely tower above the others. What exactly is the Post-War Consensus, why do people defend it so vigorously, and why must Christians question it?

The debate over the subject has certainly gotten heated. In fact, if you believe the reports, a sizable chunk of the evangelical alt-right has gone through a schism over the subject, with some anathematizing the others over what they feel to be a breach of some ill-defined new Original Sin. But if we’re to have honest discussions, and come to truthful conclusions, this term needs to be properly defined.

And as an impartial evaluator of this debate, someone who is neither a Christian Nationalist nor a (vigorous) opponent of it, my observations indicate to me, at least, that almost no one has done the work of defining this important term (or at least, have not done a good job advertising that the work has been done). And separating, defining, and dividing over a debate where terms are not defined, is tragic indeed.

To me, that’s an important fact. Good debates always define terms. Back in high school, I lived and breathed academic debate. My awards from the National Forensics League (the nationwide debate circuit) are still proudly displayed in a closed cardboard box atop a shelf in my barn somewhere. My letterman’s jacket only had one letter, and that’s for the varsity debate team (I kid you not, nerd city). And if you’ve ever watched such a debate, you know that the first minute or so in the ‘first constructive’ is spent defining terms. That’s because without terms being defined, the debate could quite easily be equated to two ships passing in the night.

WHAT MANY ASSUME THE POST-WAR CONSENSUS TO BE

If you watch the debates in evangelicalism, you’ll ascertain a common presumption that “Post-War Consensus” is short-hand for “the Holocaust.” As in, “If you deny the Post-War Consensus, you deny the Holocaust.” Or, “If you question the Post-War Consensus, you question the Holocaust.”

As I’ll explain in a moment, this isn’t only reductionist (which is when you take something that’s complicated and reduce it to something much simpler), but it’s beside-the-point. For it to be reductionist, the Post-War Consensus would have to have the Holocaust as at least a tertiary part of the main point. But the Post-War Consensus can’t be reduced to merely the Holocaust, because the Holocaust isn’t even ancillary to the Post-War Consensus. It’s not entirely relevant.

In a lot of ways, we have Douglas Wilson, James White, Tobias Reimsdeckerhemierschmitt to thank for this because when - in the Antioch Statement - they collaborated to condemn the “questioning of received accounts,” that was their short-hand for “Holocaust denial” or “rethinking Hitler.” In attempting to take the position of established wisdom, they profaned the concept.

If you appreciate my work, please consider getting a paid subscription to access exclusive content. This is one of the things I do to provide for my family, so I sure appreciate it.

Like all terms, the Post-War Consensus has an established meaning. When anti-Christian Nationalists started using the term, they did it in a way that was foreign to the definition historically given it. The term isn’t a historic recollection of facts (like “six million Jews died in the Holocaust” or whatever other thing we’re mysteriously compelled by the Holy Ghost to believe without question or asterisk). It was an economic and political term.

The consensus that we’re speaking of did not relate to whether or not Hitler was a bad guy, or how wooden doors on gas chambers would make a seal for Zyklon B gas, or how fingernails leave discernible indentions in dried cement. That consensus isn’t about whether or not Britain blockaded and starved Germany, or the designation of Joseph Stalin as a good guy somehow.

Rather, the Post-War Consensus was a British political slogan defining a political position, much like “The Monroe Doctrine” or “Manifest Destiny” is in America). Clearly, when the term was was first applied in 1945 Great Britain, the Limeys weren’t close to siding with Hitler.

No, the term was used to express a metaphoric rubber-stamp to the Labor Party to implement liberalized economic policies in Great Britain, using the war as the precipitating reason for these changes, with the term “consensus” being more hopeful than accurate. It was, from the beginning, propagandic. The messaging to the British people was, “We all agree on these changes,” despite that not being altogether true.

The economic and political changes the Post-War Consensus referred to was the nationalizing of trade unions, the creation of the modern welfare state, and the creation of the universal medicine. One wonders what, if anything, that has to do with details related to the Holocaust.

Largely, most believe the Post-War Consensus was a consensus, but it was in the majority until the victory of Conservative Party leader, Margaret Thatcher, in 1979.

AN EXPANDED VIEW OF THE POST-WAR CONSENSUS

Only in recent years, mostly starting in 2016 with the election of Donald Trump and the populist revival that led to Brexit and similar movements in Europe (which has now spread to South America), the “Post-War Consensus” has been expanded to include the world order that developed after the end of World War II.

In other words, the term “Post-War Consensus” as we are using it now, has been a recent invention. Desiring to stop the growth of populism around the world, the term has been back-dated to refer to cooperation between nations as it pertains to the international order. This is covered well in the book, Return of the Strong Gods, by R.R. Reno.

Rather than dwelling on the corruption of the term, Reno simply goes with the flow of propaganda and addresses it head-on.

The Post-War Consensus, since the term’s commandeering, has come to describe a supposed consensus that existed among the nations in the Post World War II era, designed to hold-off the various ingredients of world conflict that savaged the planet during both the first and second world wars.

According to Reno, the so-called “strong gods” are strong leadership, a commitment to national interests and political nationalism (the belief that governments are instituted to protect the rights and interests of their citizens, in particular, and to the exclusion to those of people of other nations), closed borders (which maintain uniform religion, values, and ethnicity in order to sustain high-trust societies), and cultural hegemony or cohesiveness (another word for this is patriotism).

Rather than acknowledge that World War II had a context (which was a conflict of competing national interests between Great Britain and Germany), or that Hitler’s rise had a context (chiefly, the German people feeling marginalized and humiliated by the treatment they received after World War I, or their belief that the Weimar Republic was essentially a foreign, occupying force that didn’t care for the German people), the Post-War consensus painted a reductionist view. And that reductionist view was that the war was caused, simply enough, by strong national leaders (Hitler and Mussolini) who cared too much about the needs of their own people (and cared not enough for others).

The antidote to all of this, the new Post-War Consensus claims, is to usher in the reign of the weak gods, which are neo-liberalism, open borders, open trade, and the concept of global citizenship. In additional, weak national governments must be replaced by strong global or regional governments that blur the good of people belonging to a particular nation, in deference to the needs of a group of nations.

Of course, this largely was a post-war consensus, but it was not the Post-War Consensus (meaning that the term was newly redefined).

Reno argues that the weak gods are just as tyrannical as the strong gods, but considerably less competent. I’m not opining on that here.

If you don’t want to deal with a subscription, consider a one-time gift of your choosing by clicking below.

POST-WAR CONSENSUS IS GLOBALISM

The blue-print for globalism (as defined by the things created by the weak gods), was laid out pretty explicitly in the post-war era. They were not, of course, a consensus at all. But those ideas did win, as you see in the establishment of European Union and the intentionally-broken immigration system in the United States. You can also see that the side won in the world’s education system and propaganda mills, which have churned out the idea that enlightened, peaceful, kind people must de-value an “America First” mindset and submit their needs to whoever in the world would like to pilfer their nation. Because the “victors write the history books” (a phrase un-ironically coined by Winston Churchill), it certainly seems there was a consensus (but it has been a never-ending struggle).

Largely, the world’s post-war economy has been built upon the precepts of globalism. Industries and extremely wealthy individuals alike have invested fortunes in a global economy, under global (or regional) government, treating human beings as products to be taken to market (migration), and viewing the interests of business above the interests of individual citizens of any given nation. It’s on this point that Reno argues our new overlords - industry and special financial interests instead of strong national leaders - are just as brutal.

The blueprint for globalism piggy-backing on the post-war era was laid out by numerous prominent thinkers in academia, including the Austrian-born philosopher, Karl Popper. The term he used to describe this “open,” borderless, effectively nationless world that would usher in peace and prosperity was “Open Society.”

OPEN SOCIETY

If the term Open Society sounds familiar, it’s because that’s the name of George Soros’ international nation-pilfering organization. Americans might know him for funding migrant caravans to come to our border from Central America. Or, we might know him for funding the election of prosecutors to our major cities who refuse to prosecute crime (unless it’s little old ladies praying outside abortion clinics). But the British know him as a man who short-sold the Bank of England, and almost collapsed their national currency (which he did on purpose). Soros is not allowed in several countries around the world because he’s been identified as hostile to their national interests, including Poland, Hungary, Russia, Turkey and others (the “fact-checkers” on this are lying, in part because the are - unsurprisingly - funded by the Open Society Foundation).

Make no mistake about it; Soros is a wanted man in numerous countries for his crimes against those nations. His desire, which is to promote the expanded definition of the Post-War Consensus, is to topple even the idea of nationhood. And also un-ironically, criticism of Soros is called “anti-semitic” because questioning the Post-War Consensus and Open Society has something to do with Hitler (so they tell us).

In Popper’s “Open Society” concept, which he laid out his 1945 The Open Society and Its Enemies, he asserts that the old world order was centered on the needs of nations, which closed them to the interests of others. But if the world could embrace a truly “open and free” society, a New World Order could arise to bring a period of extended peace and prosperity.

QUESTIONING OPEN SOCIETY = QUESTIONING THE POST-WAR CONSENSUS

Under this heading, I’ll have to leave most for another time. For now, it suffices to ask if you - the reader - feel if the Open Society experiment has led to greater peace and greater prosperity in whatever nation you’re reading this in. Has Popper’s experiment worked? Have wars decreased? Has quality of life increased for those in industrialized nations? Is the First World better than it was before?

Judge for yourselves, and that will inform you as to whether or not you want to question the Post-War Consensus.

EVANGELICALISM’S FAKE POST-WAR ARRANGEMENT (CONSENSUS) DEBATE

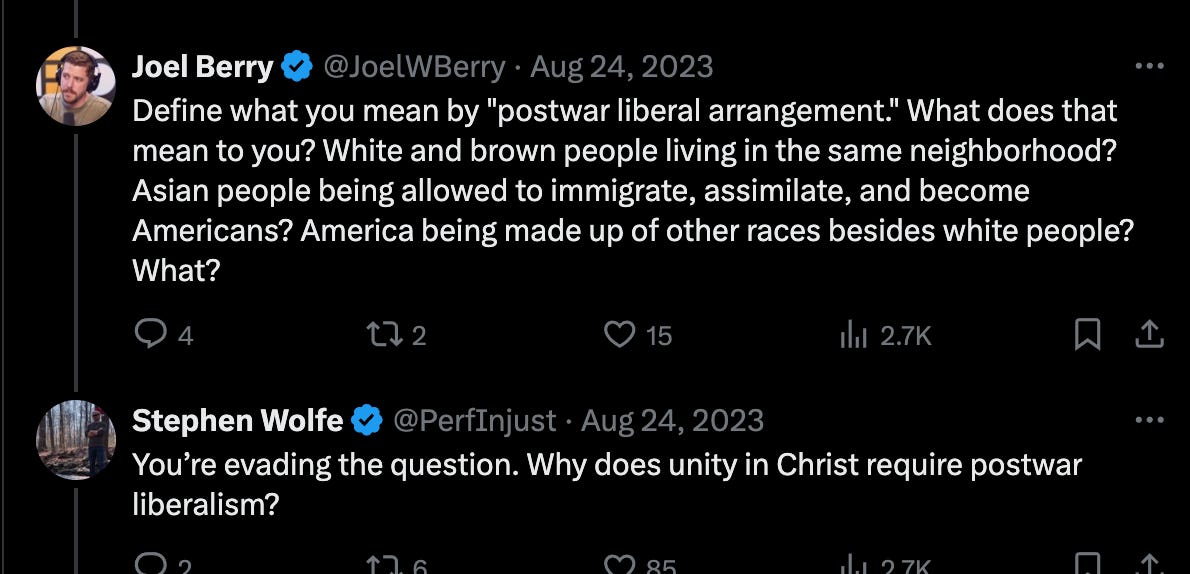

Its peculiar use and its foreign, misapplied definition in evangelicalism was traced by The Federalist to a question posed by The Babylon Bee’s Joel Berry to Stephen Wolfe.

Berry asked Wolfe, a prominent Christian Nationalist, or XNat, for short…

“Define what you mean by ‘postwar liberal arrangement.’ What does that mean to you? White and brown people living in the same neighborhood? Asian people being allowed to immigrate, assimilate, and become Americans? America being made up of other races besides white people? What?

The context of the conversation centered on Christian Nationalism, which shows you exactly how much evangelical skirmishes affect the Public Marketplace of Ideas. As you can tell from Berry’s comment, it has something to do with ethnicity (presumptuously). Ironically, Berry has played a prominent role in accusing Christian Nationalists of innate bigotries.

He followed up by saying…

Chiefly the argument, although cloaked in the disguise of a theological spat, was whether or not Americans have a duty to care about the interests of primarily Americans.

And then, a further debate must occur, once that question is asked. And that question leads to, “What is an American?” The answer, one would think, is that an American is someone who is from America and someone who is for America.

But because the weak gods sit upon the thrones of Olympus, the question is then construed as, “Do you mean white people?” And this is the classic bait-and-switch away from a discussion that might lead to valuable discussions on the nature and value of nationalism, and toward an uglier conversation about race.

The notion that Christian Nationalists are caught up on race is largely a canard, a rhetorical ploy. As you can see from Berry, it’s the anti-Christian Nationalists that tend to make things about race (which is pretty dang woke of them). They bulldog the issue incessantly, trying to take complex arguments about the ontology of citizenship, and extrapolate nothing but the vulgarness of race. In doing so, they accept a recently new and novel definition of race, which until recently, was not limited to skin color, DNA, or melanin count. Not long ago, the concept of “race” dealt primarily with nationhood. This is why, in books written before 1950, you see references to the “American Race” (or the British Race or the French Race, etc) which was altogether devoid of a discussion on ethnicity.

Sadly, there are some who side with Christian Nationalism who believe the lie that ethnicity is a synonym for race, and no shortage of bots (some are human, some are machine) that use it as an opportunity to espouse racialism, which is equally as unhelpful as Berry. This further exemplifies the difficulty of having beneficial conversations on the subject of nationalism vs globalism.

REDUCTIONIST DEFINITIONS OF POST-WAR CONSENSUS

If you’re tracking, Post-War Consensus war originally limited to discussions of British domestic policy. Decades later, the term was back-dated to refer to the merits of Open Society Globalism (which indeed existed back then, but was not attached to the term). But now, the definition has shrunk back smaller than ever, and is defined as “The Holocaust.”

This was likely the definition of “received accounts” as spoken of by Wilson. To so many, questioning the Holocaust is not only the primary matter for the Post-War Consensus, it’s the only one.

The craftiness of this reduction is clear; if you question the Post-War Consensus, then you’re a Holocaust Denier. And just like that, all the valuable conversations that evangelicals need to have about what type of international order is best, or if no international order is best, and that perhaps society is best organized by independent nation-states, is limited to talk about Nazis burning Jews in the ovens.

It’s hard to have reasonable discussions about Open Society and the New World Order when it’s overshadowed by sticky subjects that are so prone to volatility. But that’s the point of the bait-and-switch. That’s why the bait-and-switch is offered. There are powerful forces at play that don’t want evangelicals to question the “received accounts” propagating global governance.

Berry, and indeed many anti-XNats, are probably unaware that the Post-War Consensus has little to do with the Holocaust, if anything at all. And many XNats, similarly, are perplexed at having to sign the dotted line on a matter of historical claims about an event that happened from 1933 to 1945 Germany. Most are unwilling to have a discussion on the Post-War Consensus if it involves the insinuation that by doing so, you somehow support Adolf Hitler.

And I repeat; that’s the point.

I know this will shock some of my friends, but I don't actually have to hold the political beliefs of FDR, Harry Truman, and Karl Popper to oppose Hitler (or his evil twin, Stalin).

I'm not sure why some of them are signing up for that.

I found this article to also be constructive in understanding the PWC from an American angle. https://theaquilareport.com/the-post-war-consensus-controversy-another-perspective/